With a combined total of over 300 participants from around the world, the conferences showcased a wide range of high quality research into mitochondrial disease, including genetic diagnosis, potential therapies and updates on clinical trials. We also had an opportunity to meet with our Lily-funded researchers, mitochondrial experts and patient organisations from across the globe.

New diagnostic tools

Transcriptomics and proteomics

The first two presentations at the Neuromuscular Translational Research Conference were given by Prof Rita Horvath from the Wellcome Centre for Mitochondrial Research at Newcastle University and Dr Holger Prokisch from the Institute of Human Genetics at Technical University Munich in Germany. Both talked about the challenges of diagnosing mitochondrial disease and how this can be improved by combining different diagnostic approaches.

These approaches include Whole Exome Sequencing (the method used by the Lily Exome Sequencing project) which allows thousands of genes to be analysed at the same time to try and identify the genetic change (mutation) that is causing the disease. While this method has been successful for many of our families, it does not identify the causative mutation 100% of the time and so additional techniques, known as ‘transcriptomics’ and ‘proteomics’, are currently being investigated to improve the diagnostic rate. This combined ‘multi-omics’ approach allows the sequence of the genes to be studied alongside what is produced by the genes, and has already helped identify genetic changes that cause mitochondrial disease.

Biomarkers

Another approach that can help in the diagnosis of mitochondrial disease is the use of naturally occurring molecules, also known as biomarkers, which are found in the blood and can be indicative of a particular disease. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-21 and growth differentiation factor (GDF)-15 are metabolic hormones (proteins) that have been shown to be useful biomarkers of mitochondrial disease but their use may be limited due to increased levels of these seen in other diseases.

To address this, Dr Ryan Davis from the Kolling Institute at University of Sydney in Australia presented his research at the Mitochondrial Medicine meeting that identified a number of different metabolites that could be used to improve the diagnosis of mitochondrial disease. Further development of this approach could allow for rapid frontline diagnostic testing for patients showing symptoms of mitochondrial disease and could help identify those who would benefit from genetic testing.

Genetic Diagnostics in Oxford: a 25-year journey

One of the platform presentations at the Neuromuscular Translational Research Conference highlighted the major advances in the diagnosis of mitochondrial disease and was given by Carl Fratter, a Clinical Scientist who leads the mitochondrial genetics team within the Oxford Medical Genetics Laboratories. Carl gave a fascinating overview of how the diagnostic service has developed since it was established by Prof Joanna Poulton in 1988, including a brief history of the techniques used for diagnostic testing and how they have changed dramatically over the years.

He emphasised the importance of the NHS Highly Specialised Service for Rare Mitochondrial Disorders, which was established in 2007 with centres in Newcastle, London and Oxford, and stated that collaboration between the three centres has been key to developing the service and enhancing knowledge of mitochondrial disease. For more information visit http://mitochondrialdisease.nhs.uk/.

New therapeutic approaches

Reactive oxygen species (ROS)

Dr Mike Murphy from the MRC Mitochondrial Biology Unit at the University of Cambridge talked at the Neuromuscular Translational Research Conference about ‘reactive oxygen species’ (ROS) produced by mitochondria. These unstable molecules can damage cells and impair the ability of mitochondria to make cellular energy. It has long been known that increased levels of ROS can contribute to tissue damage seen in many different medical conditions, including heart attack and stroke. By finding out the mechanism behind this ROS production, Dr Murphy now hopes to develop new therapeutic approaches that could reduce the damage caused by ROS, which could potentially benefit patients with mitochondrial dysfunction.

Nicotinamide riboside (NR)

Dr Rong Tian from the Mitochondria and Metabolism Center at the University of Washington in Seattle presented some work on nicotinamide riboside (NR), a form of vitamin B3 that has been shown to increase levels of an enzyme called NAD+ (nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) in a mouse model of mitochondrial disease. NAD+ is important for energy production and, at increased levels, has been shown to improve some of the clinical features seen in the mice, which included an improvement in heart function.

Dr Tian discussed a study that looked at the effects of NR in healthy volunteers and reported higher blood NAD+ levels in some individuals. This suggests that NR could potentially be used as a therapy in patients with mitochondrial dysfunction and there is currently a clinical trial to address this in patients with heart failure. Importantly, The Lily Foundation are also funding research to improve the uptake of NR into the bloodstream and maximise the positive effects it has on mitochondria.

Protein replacement therapy

Professor Haya Lorberboum-Galski from the Institute for Medical Research Israel-Canada at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel talked about a novel concept they have developed for the treatment of mitochondrial disease using a technique called ‘protein replacement therapy’. Proteins are the ‘building blocks’ that make up our body and the instructions to make them are found within our DNA. When there is a genetic mistake within the DNA, this can result in a faulty protein being produced within cells that can contribute to the symptoms of the disease.

Professor Lorberboum-Galski’s research aims to replace faulty proteins involved in mitochondrial function with a normal version of the protein, which is done by creating a ‘fusion protein’ that enters the mitochondria and is used instead of the faulty protein. Experiments in patient cells and animal models have shown encouraging results and work is now underway to develop fusion proteins for human use.

Genome editing

Another exciting talk was given by Dr Payam Gammage from the MRC Mitochondrial Biology Unit at the University of Cambridge who presented some of his recent research investigating the potential of genome editing as a treatment for mitochondrial disease. The overall aim of this technique is to remove faulty mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) from the cells of patients with mitochondrial disease using ‘molecular scissors’ that cut the mtDNA. This causes the faulty mtDNA to be removed from the cell but leaves the healthy mtDNA untouched.

Experiments in cell culture models have revealed that the overall result is a decrease in the level of faulty mtDNA combined with an increase in healthy mtDNA, which could potentially lead to an improvement in the symptoms of mitochondrial disease. Dr Gammage discussed some promising developments in this area, with positive results from a mouse model of mitochondrial disease.

Clinical trial updates

The last session of the Mitochondrial Medicine meeting provided some interesting updates on clinical trials for mitochondrial disease. Dr Magnus Hansson from NeuroVive Pharmaceutical AB in Sweden reported that a first in human study to investigate the safety and tolerability of KL1333 had just been completed in healthy volunteers, with plans to start the next phase of this trial.

Dr Amel Karaa from Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, USA, presented the findings of a phase 2 clinical trial of elamipretide (MMPOWER2) and talked about RePOWER, a multi-national pre-trial registry of patients with mitochondrial myopathy. Patients enrolled in RePOWER are eligible for recruitment into an ongoing Phase 3 trial (MMPOWER3), with results expected in 2019. Dr Miran Janssen from the Radboud Center for Mitochondrial Medicine in Nijmegen, The Netherlands, also presented the findings of a phase 2 clinical trial of KH-176 (KHENERGY). Given the relatively short duration of this study, the findings were encouraging and preparations are underway to begin a phase 3 trial.

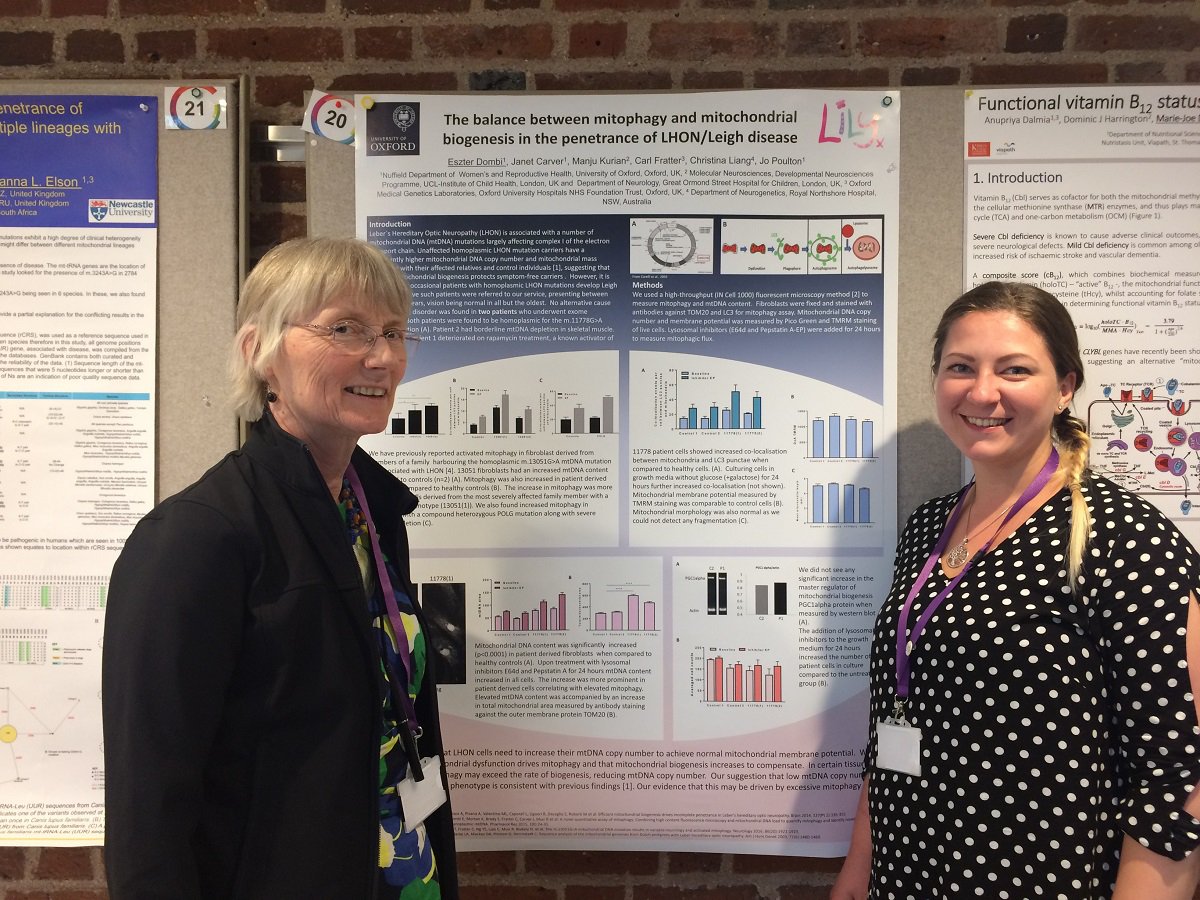

Both conferences provided a great chance to hear about some of the latest research into mitochondrial disease. As well as the speakers, there were also over 100 scientific posters covering various aspects of mitochondrial disease research, which included posters by Lily-funded researchers Dr Olivia Poole, Dr Kyle Thompson and Eszter Dombi.

Our Lily Foundation stand at both conferences gave Alison and Lyndsey a fantastic opportunity to chat with clinicians, researchers and pharmaceutical companies about the work we do and the research we fund, which wouldn’t be possible without our dedicated supporters. It was also wonderful to build on our strong relationship with many mitochondrial disease experts from around the world, as well as members of the International Mito Patients.